A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K • L

M • N • O • P • Q-R • S • T • U • V • W • X-Z

Welcome to the Lincoln Cent Forum Glossary.

Use the alphabetical links above to navigate to the desired term.

This glossary of terms was written and compiled by Will Brooks with the help of our forum members. A huge thanks to everyone who contributed knowledge, ideas, words, and photos to make this growing educational resource possible. Special thanks to Richard Cooper, aka “Coop” who donated many of the photos.

S Mint Mark: Cents struck at the San Francisco Mint bear an S mint mark below the date. Business strike Lincolns were struck at the San Francisco Mint from 1909 until 1974, except for 1922, 1933, 1948-1951, and 1956-1967. Also, starting in 1968 and continuing to the present, proof cents also exhibit the S mint mark. One notable exception is that in 1990, some proof sets contained a cent that was missing the S mint mark. These carry a strong premium. Please see Jason Cuvelier’s excellent tutorial on S mint mark styles Here.

Saddle Strike: When a planchet is far enough off-center out of the collar that two different adjacent die pairings strike it at the same time leaving two completely separate partial strikes on the coin. There area on the coin between the two strikes sometimes buckles upward resembling a saddle.

Sand Cast Counterfeit: See Cast Counterfeit.

Satin Finish: The mint has made several special issues of uncirculated and proof cents that have a “satin finish.” Special preparation of the dies give these cents less glossy fields. These special satin finish issues began in 2005 and ended in 2010. There was also a 1936 proof cent issue with a satin finish.

Seigniorage: This is the difference in the face value of a denomination and the actual cost to produce and distribute it. This is an important issue in the debate over continuing the production of Lincoln cents, and the potential materials that may be used in their future production.

Semi-key: The “2nd tier” of difficult issues in a series to collect due to rarity and price. The very most difficult to obtain are considered key.

Series: The complete chronological run of a particular denomination or sub-denomination. For example, the Lincoln cent series runs from 1909 until the present, while the wheat cent series runs from 1909 until 1958.

Series Doubling: See Reduction Lathe Doubling.

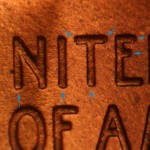

Serif: An extension, base, or flourish often seen at the end of , and coming off at an angle to, a letter stroke. Doubled dies and re-punched mint marks can often be identified by a split in a letter’s serif.

Separation Lines: See Division Lines.

SG: See Initials.

Shattered Die: A die that has suffered one or more major rim-to-rim die cracks, with some displacement showing on the coins it strikes. Some of these could be considered major retained cuds. A shattered die is unlikely to last through many more strikes before completely breaking into pieces.

Shield Cent (Shield Reverse): A Lincoln cent minted from 2010 until the present, bearing a reverse design featuring a shield. This reverse design was created by artist Lyndall Bass, and sculpted by Joseph F. Menna, both of whose initials appear on the reverse of these cents.

Shifted Hub Doubling: Also called a class 9 doubled die, this is strictly isolated to the single squeeze era. It is surmised that as the pressure increases during a single-squeeze hubbing, that die can slightly shift into its final position, leaving some doubling. Since blank dies are convex, class 9 doubling usually manifests on the central design elements, especially the 6th and 7th columns on the reverse of Lincoln memorial cents, and on the left hand of Lincoln on the Formative Years in Indiana reverse.

Single Squeeze: Single-squeeze hubbings began experimentally in the 1980s and became the exclusive method for hubbing dies by 1996. Before that, dies had to be hubbed multiple times to get an acceptable image on them for striking coins. By hubbing a die in a single attempt, the mint hoped to eliminate doubled dies from happening. However, this method ended up creating a new class of doubled die called shifted hub doubling, or Class 9 Doubled Dies.

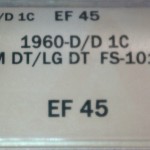

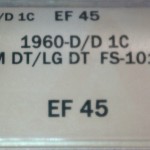

Slab: The colloquial term for the plastic holder that third party grading services put coins into after grading and/or attribution. The holder will generally have the coin’s grade and/or attribution number labeled on it.

Slide-type Machine Doubling: See Machine Doubling.

Small Date: In the Lincoln cent series there are 4 years that saw a mid-year design change in the font of the date, resulting in Large Date, and Small Date issue varieties released within those years. Those years are 1960, 1970 (S mint mark only), 1974, and 1982. Please see Jason Cuvelier’s excellent tutorial on the subject Here.

Special Mint Set: From 1965-1967, the mint did not issue any proof sets. They did, however, issue these “Special Mint Sets” during those years featuring a cent, nickel, dime, quarter, and half in a plastic holder. These were not proofs, but they were struck with specially prepared dies and under higher pressure creating very well-struck coins. Coins from these sets are often called “SMS” coins.

Specimen: Any individual coin, as an example of a particular issue variety, die variety, or error.

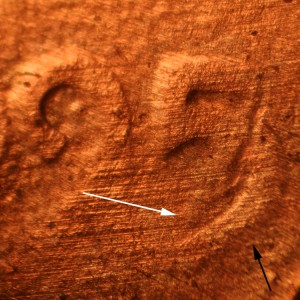

Spiked Head: The skull region of the bust on Lincoln cents is a common area for Die Cracks to develop. See also Cracked Skull. When these die cracks extrude out of the skull into the field, they are colloquially called “Spiked Heads.” Jean Cohen lists Spike Heads in her book “Errors on the Lincoln Cent.” Photo courtesy of forum member duece2seven.

Split Die: A die that has been bisected by a rim-to-rim die crack that extends deep enough into the die to cause lateral displacement, leaving a gap in the die, which will show as a wide unstruck raised ridge on a coin.

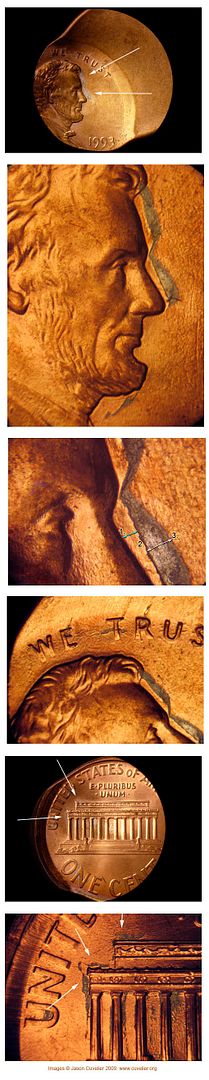

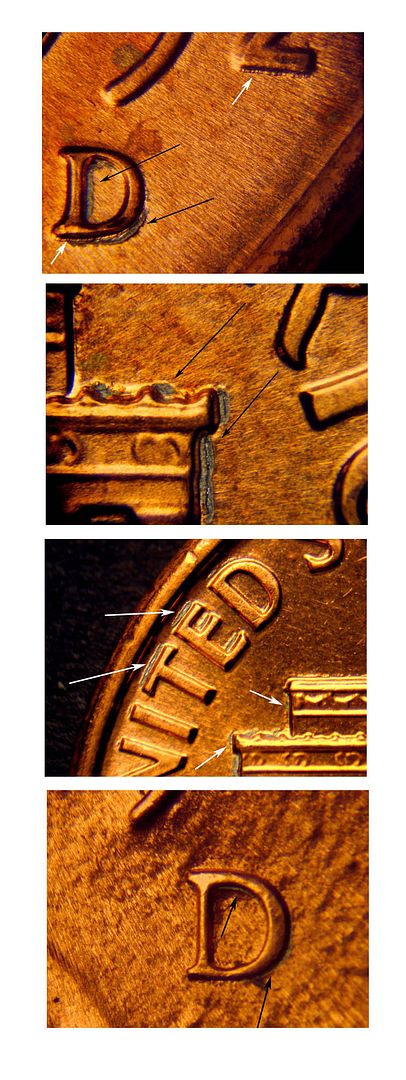

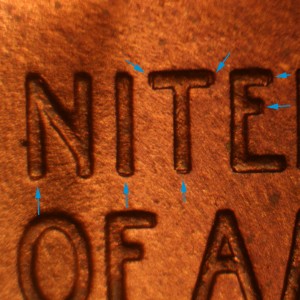

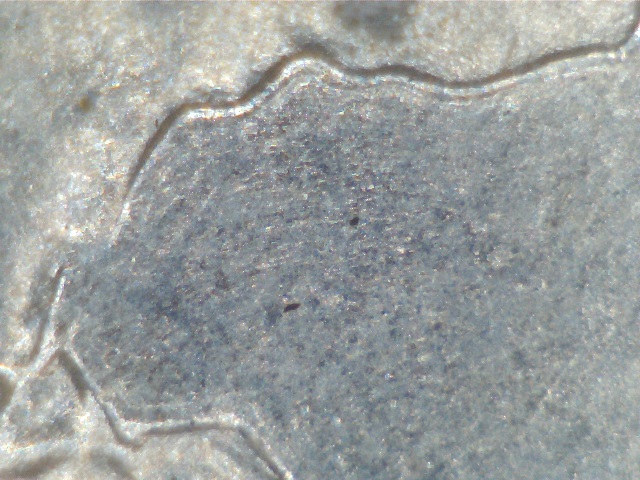

Split Plate Doubling (Split Line Doubling): This occurs only on copper-plated zinc cents struck from mid 1982 to the present. During the striking of plated cents, the plating is stretched in order to form the raised design elements. Whenever relief is created from a flat surface, there must be expansion of the overall surface area, thereby putting stress on the plating. Sometimes, the plating will split on the rim-side of the devices, exposing the zinc core. The exposure will be in the same shape as the design elements, thereby creating a “doubling” effect. The exposed zinc is blue-ish in color. In addition to the examples shown below, please also see Jason Cuvelier’s thread on the subject Here:

Split Serif: A doubling effect on the serif of a letter as a result of hub doubling or re-punching.

Squeeze Job: See Garage Job.

Steel Cent (Steelie): A cent minted in 1943 which had a steel core plated with zinc. This was done due to a shortage of copper during World War II. A Steel cent should weigh 2.7 grams and be strongly attracted to a magnet. A large number of these cents were re-plated outside of the mint in an effort by people to make them look uncirculated. There were also a very small number of steel cents accidentally struck in 1944. Beware of re-plated copper cents and altered cents from other years. A re-plated copper cent may stick slightly to a magnet, but not with the same strength as a genuine steel-core cent.

Stiff Die Fill Raised Design Element Doubling: See Grease Mold Doubling.

Straight Clip: See Clipped Planchet.

Strike: The moment when the dies hit the blank planchet, thereby creating the design in relief on the coin.

Strike Doubling: See Machine Doubling.

Stripped Plating: When the copper plating is removed from the zinc core of a cent using chemical or mechanical means. This seems to be a popular science experiment in recent years. One must be careful to not confuse a stripped cent with a genuine unplated cent. The former is post-strike damage, while the latter is considered a mint error. A genuine unplated uncirculated cent will still have mint luster, while a stripped one will not. Also, some of the methods for stripping a cent, such as hammering it between leather to split the plating, will leave the cent with a larger-than-normal diameter, sometimes referred to as a “Texas cent.” For more information on stripped plating vs. unplated mint errors, see Jason Cuvelier’s tutorial Here.

Struck Counterfeit: A counterfeit coin made by using dies to strike blank planchets, as opposed to a cast counterfeit, which is made by pouring metal into a mold. To identify struck counterfeits, one must be very knowledgeable of the specifications and design attributes for that issue, since struck counterfeits will exhibit flow lines and a lack of pitting, just like a legitimately struck coin would.

Struck Through: A struck-though error happens when a foreign object gets between the dies and an unstruck planchet. When the dies strike the coin, the foreign object will also be struck into it, leaving an incuse impression in the coin. The “foreign object” may be anything, such as cloth, wire, grease, dirt, metal scraps, or even another coin which had stuck to one of the dies, called a die cap.

Struck Through Filled Die: The most common form of struck through, a cent that is struck though a filled die will have missing or weak design elements. Since that portion of the die is filled or clogged with grease or dirt, that portion of the design will not be struck on the coin. Although this can affect any portion of a coin, some of the more well-known instances in the Lincoln series are the 1922 “Weak D” cents, as well as some of the “no FG” cents.

Struck Through Late Stage Die Cap This is a coin that was struck by a capped die which has already struck many other coins. The face of the die cap gets thinner and thinner with each strike, as it expands outward. After striking so many additional planchets, the face of the die cap will be thin enough to allow parts of the normal die design to appear on the struck planchets, yielding a ghost-like image of the bust and other devices. As the die cap continues to strike coins, more and more of the normal design elements will show on the struck coins until the die cap completely deteriorates away. Photos courtesy of forum member Joel.

Sunken Die: See Die Subsidence.

Superb (BU): A subjective term referring to the highest end of the mint state scale (MS 67+). “Gem” is higher than “Choice,” and “Superb” is higher than “Gem.”